Harvey Kurtzman: Mid-century’s Mad Man of Comic Book Art Direction

It's exceptional for a comic book figure to be called “the spiritual father of postwar American satire and the godfather of late-20th-century alternative humor.” But that's exactly what Steven Heller stated in his recent review of the book The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics. Kurtzman holds a singular position, even among other comics masters. In the course of his career he created, edited, wrote and, along with other artists under his supervision, drew for publications that had modest readerships in their day, but have since acquired legendary reputations. He started Mad in 1952 as a dime comic, and followed with Trump, Humbug and Help! In those pages he would produce satires and parodies that mercilessly mocked the most cherished cultural clichés of the period. But he fell victim to one cliché himself, in that what he really wanted to do was direct.

During a panel devoted to Kurtzman at this summer's San Diego Comic-Con, Nellie Kurtzman said of her father, who died in 1993 at age 68: “He wanted to be a filmmaker, and I think that influenced everything he did.” She also recalls Terry Gilliam, of Brazil fame, saying that he saw Kurtzman “staring from the outside of the film world and wanting in.” And when I recently spoke with Adele Kurtzman, Harvey's wife, she remembered, “At the memorial service, Terry said he would have been a terrific director. That was very touching.”

A Harvey Kurtzman drawing for cover of Mad #1, 1952 (left) and a page from “Christopher's Punctured Romance” fumetto starring John Cleese, Help!, 1965 (right).

When I asked Adele about the roots of Harvey's movie aspirations, she said, “When they did the fumetti, he directed those. Although it's not anything moving, it's just panels, that was probably the beginning.” Here she's referring to a form of comics that use photos with word balloons, which he produced in the early 1960s as editor of Help!, a humor magazine. His “actors” included showbiz comedians Dick Van Dyke, Henny Youngman and a then-unknown British performer, John Cleese, who starred in a story in which he had his nasty way with a Barbie doll. Also recruited to pose were future film directors Woody Allen, Henry Jaglom and Gilliam himself, who was also Help!'s assistant editor and cartoon contributor.

In an article for London's Telegraph, Gilliam recalled his journey from college literary magazine editor to Help!: “For me, the best thing about Help! were the fumetti, the funny photo-stories that Harvey was doing. I'd never seen anything like that before. So we started doing those. That was the next step for me towards filmmaking: suddenly, we were going out and doing photo-shoots, dressing people up and finding locations and telling stories. I started sending the magazines to Harvey, because I just wanted him to see who was out there copying him, the monster he'd helped create.”

Gilliam also noted, “In many ways Harvey was one of the godparents of Monty Python.” And this merely scratches the surface of Kurtzman's legacy to contemporary humor. Either directly or indirectly, he's had an effect on everything and everybody: from Saturday Night Live to The Daily Show, from the Zucker brothers to the Wayans brothers, from National Lampoon to The Onion, and from John Kricfalusi to Matt Groening. As Arie Kaplan, a comedy writer and current Mad contributor, told me, “Harvey Kurtzman gave young comedy writers like myself a template, a blueprint for how to create meaningful, edgy, satirical comedy.”

Kurtzman's heyday began in the mid-1940s and lasted for an extremely productive two decades. But in the 1960s he began work on scripts and layouts for “Little Annie Fanny,” a sophomoric Playboy strip known more for its lavish production values than its humor. It lasted for a quarter-century. During the discussion at Comic-Con, Denis Kitchen—whose Kitchen Sink Press brought many Kurtzman classics back into print—noted how Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner took advantage of Kurtzman's career aspirations: “Harvey was seduced by Hefner. Basically, the way he was kept for years was this promise that he could direct an Annie Fanny movie.” Kurtzman had even worked with Mad writer Larry Siegel on a film treatment, imagining Suzanne Somers in the title role. But his “directing” efforts never extended further than a Spaghetti Western fumetto for Playboy that featured Tony Randall and bare-breasted women.

Marker/pencil layout (left) and color guide (right) for “Little Annie Fanny” opening page, Harvey Kurtzman, Playboy, 1962.

Kurtzman's lasting creative reputation is primarily based on his art direction. Of the 15 artists from over the past century who were selected for “Masters of American Comics,” a major museum exhibition that toured the country a few years ago, 14 were represented solely by their own work. Only Kurtzman shared his space with others who'd worked for him.

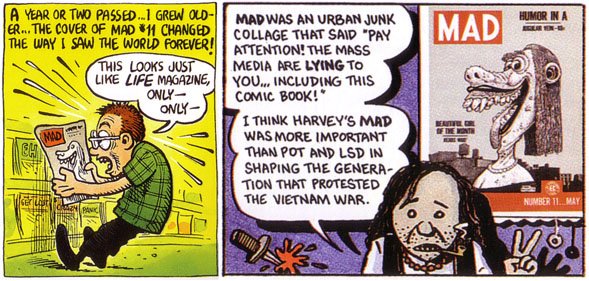

Kurtzman also had an astute eye for discovering raw talent. In the pages of Help! he gave early exposure to original underground artists Gilbert Shelton, Skip Williamson and Robert Crumb. Decades later, Crumb declared that one Mad cover he'd come across in his youth “changed the way I saw the world forever!” Mad was also a seminal influence on other cartoon talents such as Alan Moore, Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman. In his comic strip obituary for Kurtzman, Spiegelman wrote, “I think Harvey's Mad was more important than pot and LSD in shaping the generation that protested the Vietnam War.”

Panels by Robert Crumb, 1989 (left), and Art Spiegelman, 1993 (right), inspired by the same 1954 Mad magazine cover.

In the late 1950s, between Mad and Help!, Kurtzman edited two other comics publications, both of which were superior to Mad, in design as well as writing. The first, Trump, folded after the second issue. Humbug lasted 11. Despite their brief existences, they were landmark accomplishments in having expanded the parameters and potential of comic book humor. And as an independent, cooperative artists' venture, Humbug was also a prototype for the underground comics movement that followed in its wake.

Humbug was poorly printed on cheap newsprint, and surviving copies are rare. But fortunately, Fantagraphics Books has just released a two-volume boxed set of the entire run. Here, pages have been meticulously restored and re-colored from original art boards, to stunning effect. And next year Dark Horse is slated to reprint Trump, which had been financed by Hefner and luxuriously produced as a slick four-color magazine with foldout pages.

Production mechanical using knave illustration by Arnold Roth (left); illustration by Harvey Kurtzman (center); and final cover art (right) for Help! #1, 1957.

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman monograph contains biographical text and hundreds of illustrations, and spans the length of his career. Co-author Denis Kitchen hopes the book will help foster a greater appreciation for his subject's art direction skills. “Too often, especially with the collaborative work, Kurtzman's contribution is quite literally unseen,” he told me. “Harvey was masterful with compositions and the interaction of figures. Since he often worked with brilliant cartoonists like Will Elder, Jack Davis, Wally Wood, Al Jaffee and others, it's easy for a casual reader to assume they were responsible for the imagery and Harvey 'just wrote' or 'just laid out' the stories. By showing how complete and vigorous his layouts are, it's much clearer that he was a true director of the finished work.”

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman also provides ample proof that, with the possible exception of certain projects with Will Elder, illustrating his own texts was where he most excelled. Kurtzman's linework is full of vitality, with broad, sweeping strokes most likely developed during his childhood, when he'd execute comic strips with chalk on the streets of his Bronx neighborhood. Gary Groth, co-owner of Fantagraphics and editor of the 2006 softcover Harvey Kurtzman: Comics Journal Library as well as the new Humbug, is unreserved in his praise of Kurtzman's drawing. He believes it “achieves some sort of Platonic ideal of cartooning. Harvey was a master of composition, tone and visual rhythm, both within the panel and among the panels comprising the page. He was also able to convey fragments of genuine humanity through an impressionistic technique that was fluid and supple.”

Jungle Book shows “pure” Kurtzman in top form, as an innovator as well as a writer-artist. Released in 1959, it was the first paperback to contain all original comics, predating Will Eisner's “graphic novel” A Contract with God by a quarter-century. It was also rendered with a graceful finesse and written with a scathing cynicism. One of its four stories, “The Organization Man in the Grey Flannel Executive Suite,” nails down the New York marketing world of that period with a deadly accuracy equivalent to any Mad Men episode.

Like every good art director, Kurtzman was also scrupulous with his preparatory research. Kitchen, who represents Kurtzman's estate and has access to an abundance of files, observed, “It was clear from examining his complete folders on every story that no detail was left to guesswork. He would pore over the latest fashion magazines to make sure women's hairdos, clothing and shoes reflected current styles. He clipped ads for automobiles, drinks, and mundane objects so that current references were on hand for himself and his collaborators. Where historical references were needed, poor Harvey, in the pre-digital age, had to spend long hours at the public library.”

Quite a bit of Kurtzman's material is very much a part of its era, to the extent that the Humbug collection

includes 10 pages of explanatory reference annotations. Nevertheless, a substantial amount of his humor is, according to Kitchen, “timeless,” as are his ideas and insights. Referring to one of Kurtzman's Two-Fisted Tales stories from 1951, he notes, “One doesn't have to be an expert on the Korean War to be moved by a story such as 'A Corpse on the Imjin.' I would also hope that solo work such as Jungle Book will continue to have an appeal despite the topicality, in the same way that Hemingway or Chaplin deal with topicality but remain classical.”

Continuing in the same vein, historian Paul Buhle, who authored The Art of Harvey Kurtzman with Kitchen, states, “Ezra Pound wrote, 'Art is news that remains news.' And that is Kurtzman all over.”

“Kurtzman's Suburbia” sketch, Harvey Kurtzman, c. mid-1970s.